From Idea to Enterprise — Technology Transfer Tips for Academics

University researchers are probably the largest potential source of commercially valuable inventions and yet they are generally not viewed as leaders in entrepreneurial value creation. We will therefore provide some commercialization tips for faculty members as well as some suggestions for investors and entrepreneurs working with faculty members. Joining me for this article is Dr. Lorne Whitehead, a previous CEO who has spent the last 20 years combining the roles of a university professor and administrator with a high rate of patenting and spin-off company creation.

Before we begin, it is helpful to divide the path from idea to enterprise into stages. Words like invention, innovation, and commercialization are frequently used by politicians, theorists, and entrepreneurs alike to describe the act of bringing a product to market, but, as you already saw in the first article (“Start-up Fundamentals”), there are actually three distinct stages with unique requirements:

• Innovation is the process of turning an invention into a tangible product that allows people to benefit. This is not the responsibility of universities; generally they transfer inventions at this stage to existing companies or new start-ups.

• Commercialization is the engine that turns one dollar of investment into multiple dollars of return by leveraging the value of the innovative product. Larger companies are often best at this due to their inherent economy of scale and stability.

The role of university researchers is different in each stage, as you will see in the following sections.

Invention: Problems & Solutions

“Invention is 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration.” — Thomas Alva Edison

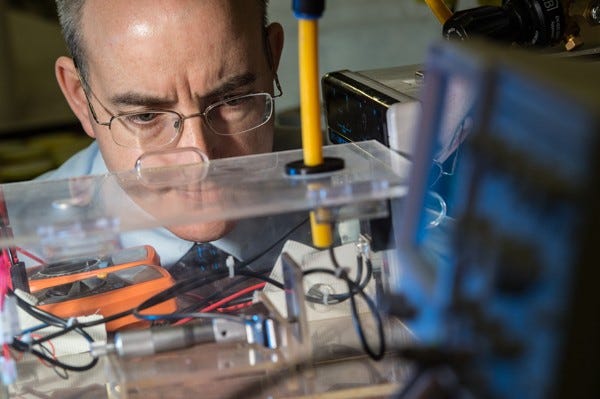

One of us (Seetzen) runs a company that helps university inventors to commercialize their ideas, and as a result he speaks with hundreds of brilliant researchers every year. This has helped build an appreciation of the great potential for universities to contribute to economic growth and societal advancement, but it can be challenging to unleash this potential.

On the positive side, universities are an ideal home for what might be called “deep invention,” which is (a) grounded in a sophisticated intellectual understanding and (b) inspired by significant societal need. One of the key challenges is to bring together these two different forms of understanding — a process that can often be accelerated through interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships, but is seldom easy. Furthermore, almost by definition, the invention process can be difficult to predict and it is usually highly recursive — multiple trips back to the drawing board are the norm, not the exception. That is why such deep invention is intrinsically difficult, and, unfortunately, it is made even more so because it runs somewhat counter to the academic mainstream.

Despite these challenges, however, universities can be wonderful places to support deep invention. They offer a powerful combination of open exchange, multi-disciplinary thinking, and relatively large amounts of flexible funding.1Furthermore, they are welcoming places for people with challenges to visit. Often industrial researchers derive significant personal satisfaction through professional interaction with the university research system from which their careers began. Ultimately, successes grow from trust between people who have different perspectives and a shared goal.

From a commercialization perspective, a key during the invention stage is to focus on the big picture without losing sight of the details. It is important to avoid limiting performance comparisons only to alternatives in the same field (e.g. “our new electroluminescent display is twice as bright as other electroluminescent displays”). That’s academically convenient, but often misleading in the commercial context. Instead, the comparison should focus on all known avenues to solve the particular problem. Having the world’s fastest horse is largely useless if people drive cars.

Once you have an idea that stands the tests of comparison to alternatives, it is time to consider protecting it. Like companies, most universities lay claim to intellectual property created by their employees. The details vary, but a common model is university ownership with proceeds being shared with the inventors. Most universities operate so-called technology transfer offices to assist their faculty with the protection and commercialization of intellectual property. The sidebar “Technology Transfer Offices” provides more guidance on engaging with such an office, which is worth doing as early as possible in the invention process.

Technology Transfer Offices

Technology Transfer Offices (TTOs) can be a powerful ally in the commercialization process if leveraged properly. To do so, faculty members need to understand three things about TTOs:

Ownership:

The university, in general, owns a significant portion of any proceeds derived from the inventions of faculty members. While this is often good value in terms of saved legal and IP expenses, inventors should keep in mind that this is ownership of proceeds related to the invention and not necessarily the commercialization. For example, if a venture is formed with the inventor as active executive and possibly investor, then the university should receive a share of the often relatively small amount of equity allocated to the intellectual property but not to the stakes given for founding, investment, or future work incentive. Most of the value creation happens post-founding, so active inventors will often receive significantly more than the initial split with the university would suggest (conversely, passive inventors will often converge onto just their portion of the IP compensation).

Intellectual Property:

Managing IP is a key function of most TTOs. They already receive a portion of the commercial proceeds, so researchers might as well leverage these skills (and funding for patents). Inventions should be disclosed to the TTO as early as possible so that a proper intellectual property strategy can be formulated. The best researchers maintain a constant relationship with specific tech transfer officers for this purpose. In my experience, patents developed by TTOs are usually solid foundations for a start-up. Patents written by independent inventors are a bit like sticking your hand into a beehive — there is honey in there somewhere but most of the time it just hurts a lot …

Commercialization:

Contrary to what one might expect, most TTOs are not actually particularly good at transferring technology for money. While well intentioned, TTOs rarely have the budget or domain expertise to do effective business development, much less fund commercialization activities such as trade shows. The average Tech Transfer Officer has 20–30 files on her desk, at best organized into broad buckets like “physical sciences,” “life sciences,” and “IT.” The same officer will have no budget to travel or reach out to a particular industry. Unless somebody walks into her office with a check, this just is not going to be enough to commercialize the invention. That is why start-ups are needed. Within the above limitations, the TTO can be of great help to researchers and especially those who are new to the commercialization process.

A special consideration for university researchers in this context is confidentiality. The very strength of universities — open collaboration and publication — can greatly undermine the value of inventions if not managed properly. The obvious step is to file a patent application before publishing your work,2 but it is also worthwhile to think strategically about communication. Collaborations add tremendous value to most research initiatives as long as the partners have a good understanding of the terms of engagement. Patent offices usually treat universities as a single institution, but collaborations with external partners should be covered by confidentiality agreements. At minimum, those should specify intellectual-property ownership and likely future avenues for commercialization to make sure that all partners are on the same page.

Done right, the above steps should yield a protected solution to a meaningful problem. The next step is to turn that solution into value through innovation.

Innovation: Start-Ups & Transfer

“Business has only two functions — marketing and innovation.” — Milan Kundera

If universities excel at invention, start-ups are the engine of innovation. The start-up environment is ideally suited to rapidly reducing risk by developing prototypes, assembling a multi-disciplinary team, and engaging with customers. This requires focus, speed, agility, and risk capital — none of which the university environment typically provides. University researchers often conceptually understand this barrier, but that does not necessarily make the transition easy.

The principal challenges in the transition are often funding and leadership. The former is a challenge because university grant funding is very different from raising venture investment. Obtaining university research grants is not easy, but imagine if grant applications happened like venture capital pitches: write a full proposal; fly to the funder’s office; realize that nobody read the proposal; explain, in 10 minutes why this research is relevant to a group of people who are at best only vaguely familiar with the field; hand over control of all material aspects of the research to the reviewers; and, finally, get rejected nine times out of ten because: “What if MIT were to start this research?” Throw in some general humiliation, and this is pretty much how venture fund raising works.3

If venture funding is already difficult, leadership is even more of a stumbling block for nascent start-ups. Unless they are willing to leave academia, it is very difficult for university professors to successfully lead start-up ventures. Even if their interpersonal leadership skills and business acumen are strong, faculty members simply do not have the required time, and, furthermore, they face multiple conflicting priorities that would inevitably make their start-up suffer. Publishing, teaching, grant writing, and many other academic duties may help fuel invention, but they cannot fuel a start-up. Accepting this is difficult for many inventors because it often means handing over control to others.

These factors conspire to make it extremely tempting for many faculty members to hold on to an emerging venture for longer than they should. Faculty-run ventures operating in university facilities with grant funding, and the unwillingness to change any of these aspects, are the dominant reason why venture investors stay away from many university opportunities — because such “research ventures” seldom generate wealth4 In contrast, spin-off companies often do.

A better solution is to make the transition gradual but deliberate. For example, Seetzen’s first venture operated in parallel to ongoing research in the originating lab for quite some time. This took the form of a modestly financed company working closely with the university lab. Critically, the former was an independent entity with its own leadership and venture financing, while the latter leveraged a large research grant to advance the fundamental science. A collaboration agreement between the company and university ensured that all university output was funnelled into the venture in exchange for equity.

The initial investment in a non-university executive for the company was small relative to the larger grant funding and workforce in the university lab, but even a small amount of professional investment made a big difference by establishing market valuation, solidifying the independence of the company from the university, and introducing commercial forces that prevented sliding back into the “research phase.” University-savvy angel investors and entrepreneurs are a great asset for this process. Earlier articles in this series that address team building provide some insight into the types of skills needed in a start-up and how to recruit the right person for the job.

Often there is an opportunity for one of the students in the project to take the day-to-day leadership role of the venture. This only works if the professor and student can truly shift their relationship to that of partners. To achieve this, the ex-student needs to step up to become a genuine leader through a mix of internal abilities and, generally, insane work hours (see the “Student Entrepreneurs” sidebar for more tips for students on this path). The faculty members need to accept that instead of a supervisory relationship, the ex-student now receives guidance from a wide range of sources of which the professor is only one. Savvy professors will actively encourage such ownership expansion of their students — this being the only way that their venture grows successfully!

Student Entrepreneurs

Students can be a powerful technology transfer driver, but being a full-time entrepreneur while studying can be very challenging (and there is no such thing as a part-time entrepreneur). Here are a few tips for aspiring student entrepreneurs:

Synergy:

Try to find work/study activities that “count twice.” For example, combine your entrepreneurial research with your graduate thesis work, or turn your company’s market research into MBA papers. This requires a bit of forethought, but the impact can be tremendous. A good supervisor, someone who understands technology transfer, can help you identify synergy opportunities and structure your program accordingly.

Goal-Optimized Schedule:

The big risk for student entrepreneurs is the lack of focus: achieving half of two goals is usually worth nothing. So you need to be disciplined with schedules and goals, and ideally declare quarterly goals in a public manner — at least to your supervisor — for that added bit of reinforcement. Keep in mind that, unlike school work, entrepreneurship leaves no room for do-overs. All exams are final, so you need to focus on delivering all the time and create an environment that supports this.

Entrepreneur-Friendly Courses:

Look for courses that are light on regular homework (weekly small stuff) and heavy on end-of-year papers (synergy!). Compact single-session courses are great because they reduce the “overhead” of course work (travel to campus, etc.). If you are doing a business on the side, you will really appreciate the blocks of uninterrupted time this will afford you.

Publishing Is Your Friend:

This applies to technical entrepreneurs and might seem counterintuitive at first glance. But a tech start-up really offers a lot of opportunity to publish papers: core principles, implementation ideas, application studies, etc. Try to attach a paper to every internal activity of your start-up. Not only is this good marketing for your venture, it also ensures that your parallel academic track does not fall behind. With the right planning and dedication, this approach will not only provide you success as an entrepreneur but also serve as a great insurance policy in the form of strong academic credentials. We have all heard the stories of drop-outs who go on to create giant companies but that’s just survivor bias. Most start-ups fail. A good foundation of education, publications, and credentials ensures that you get significant value out of your student-entrepreneur years even if your venture does not become the next Facebook.

Commercialization: Enterprise & Beyond

“Spectacular achievement is always preceded by unspectacular preparation.” — Robert H. Schuller

Once the foundation of the start-up is in place, it is time to turn on the commercialization engine. Previous articles in this series cover the key elements of product development, future financing, and exit avenues. The role of faculty members during this process is to continue to inject next-generation invention into the growing start-up. This requires a fine balance between pursuing promising research areas without neglecting the need to focus on product development. In our experience, the best way to achieve this balance is to formally separate the internal product engineering group from the semi-external research team at the university. A good Chief Technology Officer (CTO) can form the bridge between these two teams without creating undue distraction for either.

Consider BrightSide Technologies, a venture co-founded by the authors, as a highly successful example of such a partnership. The scientific foundation of the venture was developed by a group of almost a dozen academic researchers at universities across the world. Leveraging about $500,000 in corporate capital into over $3,000,000 in research funding, this team developed the vast majority of the 30 patent families as well as producing dozens of high-impact papers (a wonderful source of marketing for a technology start-up). Meanwhile, the internal team of some 30 engineers developed prototypes for most of these concepts, built a high-quality product, and ultimately brought the technology into millions of televisions through licensing partners among the largest manufacturers. Neither achievement would have been possible without close collaboration and world-class expertise on both sides.

The last step of the voyage is to turn the start-up into a stable, large company, either through growth or an exit. When that happens, the relationship between university researchers and start-up developers changes yet again. Initially, the characteristics of start-up developers will appear quite attractive to large companies: dynamic, proactive, fast, goal-oriented, etc. Unfortunately, large-scale product engineering requires discipline, precision, and process — aspects that a start-up will often deliberately suppress in order to move faster. Thus, after a brief honeymoon, “dynamic” usually becomes “can’t focus,” “pro-active” becomes “disruptive,” “fast” becomes “sloppy,” and so forth. That is why most acquisitions ultimately fail, at least in the sense of talent retention.

Fortunately, many of the above requirements are a perfect fit for university researchers. The timelines, scope, and internal dynamics of universities are often quite well-matched with those of large companies. Combined with their mastery of the technical domain, this makes university researchers the ideal technology advisors for the large company — often more so than the developers in the start-up itself. This also allows the university researchers to form relationships with the acquirer that often endure far beyond the start-up itself. Research chairs or permanent endowments provide a way for both parties to develop long-term collaborations that transfer much of the core scientific insight of the founding research group into the new large company owner. Completing the circle, university researchers can use those relationships to gain a deep understanding of new societal challenges, which they can fold back into the “deep invention engine” of the modern research university.

Technology transfer offers a great opportunity for university researchers to bring their ideas to the next level. The role of the researcher changes during the three principal stages of entrepreneurship: idea generator during the invention stage, scientific leader during the innovation stage, and, ultimately, technology advisor. Done right, faculty members can be the driving force behind start-up creation, technical growth, and even the acquisition process as long as they partner with commercialization expertise to cover the natural limitations of the university environment. (Investors or corporate development executives interested in investing in University Ventures should see the sidebar, “Investing in University Ventures.”)

Investing in University Ventures

Investing in university ventures is difficult but potentially very worthwhile. These tips might help investors or corporate development executives engaging with universities:

Know Thy Friends:

University Technology Transfer Officers are neither entrepreneurs nor lawyers, but rather a curious mix between incentive-less business developer and informal legal administrator. Most of them have a technical Ph.D. and very little off-campus work experience. Try to physically meet your counterpart early on to get a sense of their experience and listen carefully to their terminology. Universities have their own culture and vocabulary when it comes to commercialization. The more you normalize your language, the better your chances of closing a deal.

Accept Their Mission:

Ask yourself on the first day of any negotiation whether you can accept the dual mission of the university: public research and student education. Technology transfer is a subordinate goal compared to these two, so you are never ever going to get a licensing or investment deal that limits the university’s ability to conduct research, publish the results, and allow students to write their theses. Instead of fighting these constraints, smart investors will tie these needs into their company, for example, by coordinating a publication calendar as a means to conduct technical marketing.

Licensee vs. Investor:

It is truly unfortunate that most university investment deals are considered a “license.” For a traditional license, the university is usually approached by companies that want to purchase something that the university owns. The inverse is true in the venture world, where it is the entrepreneur who wants the money and the investor who has it. Unfortunately, university researchers often genuinely believe that they are doing investors a favor by taking their money. Do not get offended when this happens. It is a consequence of their sheltered reality and not intended as a negotiation stance.

Charter vs. Folklore:

Universities have a lot of fundamental charter constraints. These are unavoidable and as an investor you just need to learn to live with them. But universities also have a lot of folklore that at first glance appear like charter issues. A classic example would be the often-quoted Bayh-Dole Act in the US: “We cannot sell the technology [Charter: Bayh-Dole prohibits assignment] so we need an ongoing royalty. [Folklore: Bayh-Dole makes no provision whatsoever about payment modality.] Understanding these differences can be critical for business decisions (e.g., the inability to collect a lump sum payout would scuttle most venture investment deals for technologies with long times to market, whereas the inability to assign would not be a deal killer for the same investor). Beyond studying policy, your best bet is to ask your tech transfer officer to provide not just the “rules” but also the reasons behind them.

Risk Is Anathema:

Most university inventors are not just risk-averse.They do not just assess risk and then decide against taking it — they often genuinely do not understand the concept of risk. This usually pops up during the valuation process. Inventors, and to some degree universities, tend to over-value ideas. On the flip side, they tend to under-value human contributions. De-coupling past from future is your best bet for crossing this chasm.The past is sunk cost. The value of the invention has nothing whatsoever to do with the (government) money spent to get there and everything to do with the commercial opportunity going forward. You should therefore make a distinction between those inventors who will make substantial operational contributions post-founding and those that will not. The latter will be adequately provided for by the university portion of the deal. The former should be treated as founders with additional incentive grants.

A Manual for Venture Success

During our five-article journey through the world of venture capital, we have covered a number of important topics, including start-up fundamentals, raising capital for technology ventures, key terms and potential pitfalls, exiting with grace and profit, and this last installment focusing on academic researchers. These articles can be found at www.tandemlaunch.com. Together they form a useful guide to help would-be entrepreneurs through many of the important decisions and challenges they will meet on their journey.

Footnotes

1 Individual academics will challenge this, but remember that U.S. universities spend four times more on basic research than the entire U.S. private economy combined.

2 Publication, even on an informal basis, destroys patentability in most countries. The exceptions are the U.S. and Canada, where inventors receive a one-year grace period to file after publication. International rights are still lost, so it is still better to file before publishing, even in those countries.

3 This is why it takes on average 37 months for a first-time U.S. entrepreneur to raise venture capital.

4 As you might remember from the second article in this series (“Raising Capital for Technology Ventures,” September/October 2013), seed stage valuations have little to do with objective value but rather with investment dynamics. Whether a university concept graduates after a year or a decade of research usually does not make any difference in valuation — thus ensuring that even those faculty-run “research ventures” that ultimate achieve escape velocity rarely get any economic credit for staying on campus longer than they should have.